The art, not science, of validation

This post is in some ways, a toned down continuation of my slash and burn post from two months ago.

Lately ish, I've had a few distractions away from the Zen/Chan way of suddenness. It's not the first time this distraction has occurred. I pointed out how you should see one instead of three, because dependencies may not exist.

But what if they do?

First, double and triple check that there is indeed an inexcusable dependency, or reason, that you cannot break the speed barrier.

Yes, go and think first.

List them down inside circles. Use a pencil on paper. Draw lines between those dependencies you assume exist between each circle.

Now rub the lines off. Do those circles feel like they're comfortable just on their own?

They probably can be comfortable, but it is hard to see it.

I mentioned in my last post on how we have to align ourselves to the cosmos, based on that inexplicable human desire for 'belong-ing'.

Well, that might just be the Collectivist part of my Asian heritage coming through. I see no need for such divisions, but there are some taxanomical people who distinguish between Mahayana and Theravada schools of thought in Buddhism.

One oft used analogy is that of logs flowing down a river.

Mahayana 'Greater Vehicle' followers are like many logs. If you rotate too much, the others logs will correct you to stay on course. Theravada, they say, is like being one log. You also flow along the river to enlightenment, but if you rotate/stray too much, you may get stuck on a river bank or something.

Again, just an analogy.

There is no saying which way is better than the other, they are simply ways.

Going back to the topic for this post - what if there are things you actually do need to be aware of?

When you are one small log having to depend on a river-full of logs for guidance, how do you know you are flowing along the right track?

I'll be putting on my scientist hat for this one. Science is this crazy pursuit for the truth. Here's from a guy who got hit on the head by an apple:

"If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants."

Science may have came a long way since Sir Isaac Newton's time. Yet it is still true that almost everything we do is possible because of the groundwork someone has laid out in the past.

Here's the funny thing. There are people who make this distinction of pure vs applied sciences. Also known perhaps as theoretical science vs technology.

If we as scientists are merely standing on the shoulders of the ones before us, doesn't that mean we are taking their theories and applying them to something else? Isn't it then that there is hardly any 'pure' science around?

Granted, the 'pure' classification is usually given to the field of physics with five sigma 'degrees of accuracy' being demanded for any breakthrough. Five-sigma translates to one chance in 3.5 million that a random fluctuation would have falsified the result.

For those of us without a multi-billion dollar Large Hadron Collider though, how can we be confident of our results? What if a one sigma confidence interval is the best we can do?!!

In other words, how do we ensure that others can trust our work?

We want to stand on the shoulders of sturdy giants, not some flimsy Goliath. Especially when the going gets tough in highly experimental sciences, we need a robust way of discriminating the good ideas from the bad.

Explain why it works, or just tell me if it works!

The basis of trust is in itself, quite a philosophical question. Cassie Kozyrkov frames it well in this article when she asked this question:

Imagine choosing between two spaceships. Spaceship 1 comes with exact equations explaining how it works, but has never been flown. How Spaceship 2 flies is a mystery, but it has undergone extensive testing, with years of successful flights like the one you’re going on.

Which spaceship would you choose?

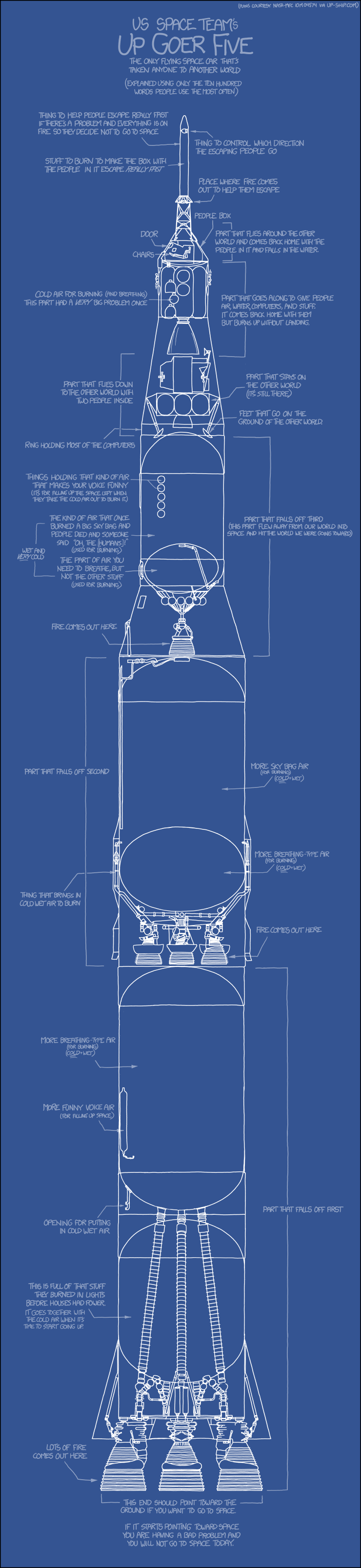

Really though, how hard can it be trying to explain a rocket?

For the short attention span people, the goal of a rocket is to get an astronaut safely from point A on Earth to point B on the International Space Station/Moon/Mars.

You can however, spend days explaining the scientific details of how a rocket works, from the mixing of breathing-type air and fire to the aerodynamics and so on. There will be teams involved in designing and making each individual component, from the booster rockets at the bottom to the astronaut-holding compartment at the top.

Would the astronaut on board care about all of the scientific details? Maybe some parts of it.

Would the astronaut care whether each of the components was tested? To some degree, probably yes.

If some underlying physical theory that could affect the rocket's propulsion system changed, would the astronaut still want to fly with it?

If some check that tests for the rocket's propulsion system failed, do you think the astronaut would still want to fly in it?

Can testing be used as a basis for trust?

Yes and no.

In tests we trust

I'll start with the yes (we can use tests as a basis for trust).

Given a complex system, be it a rocket, or an artificial intelligence (AI) system, there are many moving parts.

As with any scientific instrument, we need to ensure that it is calibrated to some standard. Technically calibration is only a subset of testing, but let's continue anyway.

Given a weight scale

When we put the IPK* on it

Then the weight scale should show 1.00kg**

- * IPK - International Prototype of the Kilogram

- ** at least until the 20 May 2019 SI base unit redefinition).

Is that enough though? For example, I could have a weight scale that simply reports 1.00kg no matter what is put on it. Much like how a broken analog clock (remember those?) can be right twice a day.

I could put 2 IPK replicas on the weight scale and if it shows 2.00kg, then that should be enough to call it a day right?

Well, you now know that the weight scale works at exactly 1.00kg, and at exactly 2.00kg. What about everything in between? What about things less than 1.00kg, or something 100kg?

A calibrated instrument gives us confidence that it works only in the environmental settings it was calibrated at. The weight scale for example, will report a value much less than 1kg on the Moon because the gravity there is weaker. And yes, it is only measuring weight (the gravitational pull of the object), not mass (the amount of matter in an object) (see Mass vs Weight).

A weight scale is actually a relatively simple instrument. Some people stand on it every day, and as much as we might not want to trust it sometimes, we know it harder ever lies (really, really?!!).

What about more complicated systems, like a car for example? You can't possibly test a car in every imaginable environment. In fact, there are environments in which normal cars just won't work, such as under the sea.

Proper testing is actually so much more than what I've just described. What well crafted tests can give you, is an assurance that it works in the specific situations it was tested in. In other words, it is designed to 'fit' a particular environment.

Taken to the extreme, systems could also 'overfit' to an environment. Someone who got carried away with the weight scale calibration process might never realize that it only works well at weights close to 1.00kg but not values a few kilograms higher or lower than that.

Overfitting is similar to memorizing. Students can certainly memorize the correct answers to the questions on a past exam paper (much like our always-1kg reporting weight scale). But they won't necessarily know what to do when the tests change!

Really though, is memorizing such a bad thing? Well, it just means that the system or model only works in a certain environment. If your weight scale is only ever going to be used on Earth, then test it on Earth, don't spend money going to outer space to test that it reports 1.00kg too.

The key thing is this:

The tests you conduct should reflect the environment in which the system will be working under.

If it doesn't, then you will need to add a new test! Testing implies using. So use that system in the new environment and see if it works!

When things go wrong

Say you have a piece of rope. You've used it plenty of times. It can carry loads of say up to 200kg, good enough for ordinary rock climbing purposes.

Now take that rope, and try to, oh I don't know, do ice climbing instead. Your rope might not be safe to use anymore. Maybe it will snap when it gets below freezing. Or perhaps some water got into it and froze, tearing away at the rope's fibres.

That's probably an obvious enough example, but sometimes things aren't so obvious. It is important that we know the limits of our devices.

And when a device is made up of individual parts, it is important to check that they work together properly. Don't just test/calibrate each individual piece and put them together hoping that it will work!

One particularly expensive failure was that of the Mars Climate Orbiter. The primary cause of the orbiter's loss was due to a mixup in converting metric and British units. That's US $125 million down the drain, I mean, lost into space, all because of a missing conversion!

Now Integration Testing could have potentially prevented mistakes similar to that. Quite often though, it takes an embarrassing mistake before people actually put the right tests in place. Try not to let that happen. Ideally, have the test in place before making it pass, something known as Test Driven Development.

You need to understand though, that tests are very superficial. Well written tests are those which fail when something goes wrong. But tests can also be made in such a way that it only checks that the output answer is correct. When things go terribly wrong, it pays to have someone who knows the mechanisms of the system inside out.

Remember that you are not just standing on the shoulders of giants, others will surely stand on yours too! Make it as clear as possible the conditions in which your work has been tested under. Context is important, so once again, tell the world where and when your model has been tested to work!

Fighting early onset satisfaction, but not too much

I get it, you've done something great, you want to show it to the world.

Professor Pat Thompson discusses the topic of early onset satisfaction well, as it applies to writing.

In academia, it doesn't help that there is a Publish or Perish culture .

Especially for myself this week, it doesn't help that I've read two pre-prints published last month strikingly close to the novel idea I'm tackling right now. That, and the fact that I've literally just cracked a significant breakthrough on my work recently.

Specifically, this seemingly simple commit in this pull request has enabled a solution to a checkerboard problem that has been on my mind (and my supervisor's) for the past two months or so.

As great as it feels to have achieved something, there is still a lot of work to do.

Validation.

I need to make sure:

- that the model itself is indeed applicable to new situations (and not just some fancy memorizing/overfitting model).

- that the solution I am presenting is better than a benchmark solution used by others in the past.

- that other people will actually be able to replicate my work to prove the above two statements are true.

The third point is on reproducibility of my machine learning workflow, the second point is on statistics, the first point is analytics. Basically the good ol' trinity of data science.

In a perfect world, you need to have all three. Not to say that any of them is easier than the other, but yes, ideally all three.

For the complicated neural network models I'm building, of course I want them to work, I want them to perform a task well! This is why we optimize them, and optimize them properly we should!

The machine learning part is not hard. The statistics are something I'm currently trying to get done, and it is basically testing that my model will perform better than a standard baseline.

Is statistics enough though, can I just do the math? And if the error is low enough, say that yep, we can push this out into the world?!

We know that the AI can do better, but we don't (yet) know why they do it.

Dangerous?

What other choice do we have?

Well, I am sort of following a Bayesian approach. Basically using data to update your beliefs. The more data we have (in the future), the better the result.

Contrast that to classical or frequentist statistics - innocent until proven guilty. You stick with the status norm (innocence, null hypothesis) until there is enough evidence (data) to refute it.

When the stakes are high, you do the best you can. Sea levels are rising after all, and lives will be affected. When time is short, compromises need to be made.

My only comfort is knowing that I have designing for a certain degree of scalability. In tests, and statistics I trust, for now.

Tis only an art, the science shall come.